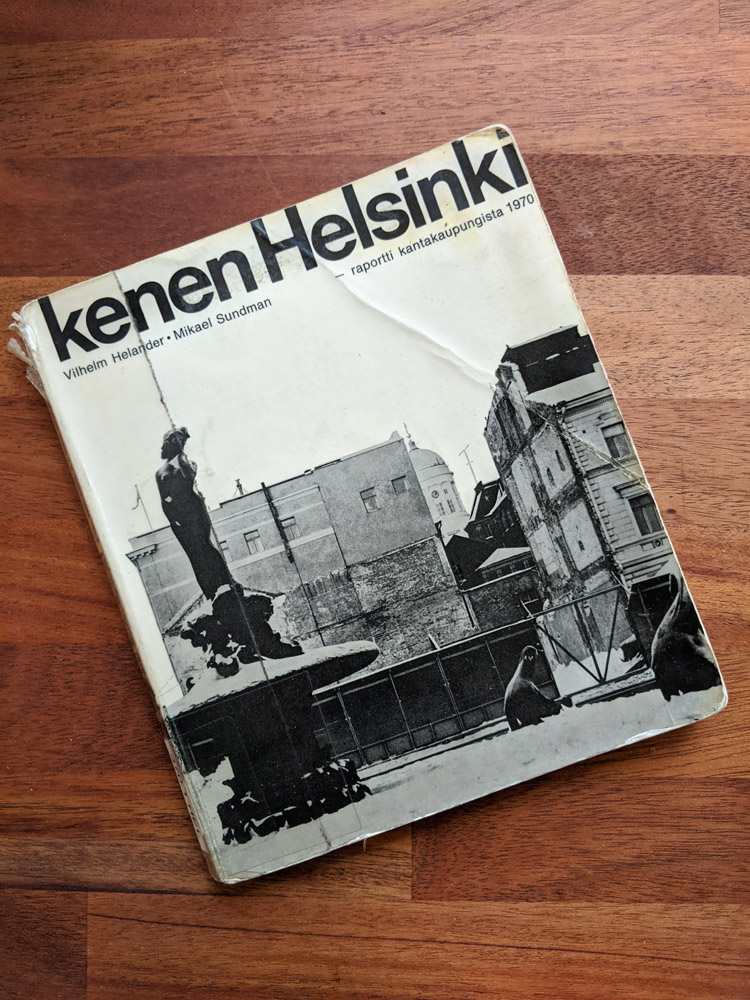

In 1970, Vilhelm Helander and Mikael Sundman published a pamphlet on the city planning in Helsinki, titled Kenen Helsinki – raportti kantakaupungista (Whose Helsinki – a report on the downtown). The pamphlet lashed car-centric planning, rampant demolition of in the downtown and undemocratic, devious, undemocratic real estate business deals of the 1960s. In hindsight, it simultaneously introduced human-centric planning, although the term was not coined yet by then. The scathing criticism of the pamphlet sunk in the leftists of the 1970. It had quite an impact, not least because it named dignitaries such as popular Prime Minister Mauno Koivisto and his share in a company planning lucrative pedestrian tunnels in the city centre. The pamphlet drove its publisher WSOY to a crisis.

Human-centric planning focuses on how people use public space instead of viewing the city abstractly as forms, demographics, infrastructure or real estate. It relies on therefore on observations of everyday life, a theme that I will open up in a forthcoming publication (related to a study on urban revitalisation with music and dance). Jane Jacobs’s had written the seminal critique on such modernist city planning, The Death and Life of Great American Cities, in 1961. It is based on insightful observations on street life. Influential studies on human-centric urban design emerged in the 1970s, such Jan Gehl’s research that culminated in the book Life Between Buildings in 1971. Helander and Sundman’s pamphlet was a timely contribution to the planning in Helsinki and it was riding on international discourse.

Watch Helander talk about the book in the 70s.

Lessons from Kenen Helsinki for today

While the pamphlet was a contemporary account of the 60s, it still offers lessons for today’s readers.

Polemical style

Vilhelm Helander had recently graduated and Mikael Sundman was a student when they wrote Kenen Helsinki. What determination they had to deliver their message. What courage to criticise planning, politics and the construction industry, to bite the hand that feeds architects. Helander, though, was probably already working on his licentiate study on renovation that was published in following year. Kenen Helsinki is then is a great example of how to make social impact with research. Perhaps the radical zeitgeist of the 60s and 70s nurtured pamphlets. There is no shortage of critical issues today, but maybe pamphlets are difficult in the modern, dispersed social media cacophony. It does favour polemic, but blurters rather than efforts like Kenen Helsinki.

The authors build their argument marvellously with a polemical style. Without any introduction, the book starts with spreads of photographs and compelling captions. Particularly before-and-after photographs are powerful. Photographs play an important role throughout, because they render broader topics of planning and conservation to concrete cases. The authors employ a captivating rhetoric especially in the image captions. They address the reader directly, typically with questions, short catchy sentences and witty wording. “A bomb? No, it is the ‘restoration’ of the city hall.” “Stockmann intends to demolish. The balconies were pulled down. The plaster decorations were taken apart. Soon you are ready to judge the building ugly and even dangerous to its surroundings. Other big companies use this method, too.”

Stories of city planning and repeating tropes

It is fascinating to read about the nearly forgotten debates, especially when they sound oddly familiar. The Finlandia hall was built controversially on valuable parkland, while historical buildings and popular cinemas were demolished in the downtown. Did you know that a skyscraper was planned to the Sinebrychoff Park? The stories in Kenen Helsinki are clashes between public and private interests. While building conservation and democratic planning are stronger today, there are comparably debatable big development projects and similar tropes are used to argument for their necessity.

When the highly controversial Garden Helsinki project in the Central Park was approved in the city council lately, Mayor Jan Vapaavuori said that any city would be overjoyed of this kind of private investment. He considers the global attractiveness of Helsinki a crucial goal. That rings a bell. Helander and Sundman write in Kenen Helsinki, how Mayor Teuvo Aura used international competitiveness to argument for building the hotels Intercontinental and Hesperia on a prime site in Töölö. A library on the site was relocated (to valuable parkland elsewhere) and the plot was leased with under-price for the hotels.

Progress in human-centric planning

Ideologies have changed since Kenen Helsinki, mostly for the good from the current perspective. Traffic planning has different emphasis today. Pedestrians are today much more considered and cycling is recognized as an important mode or transportation. Protection of built cultural heritage seems better safeguarded. There is more regulation on public procurement and possibly more vigilance for corruption. Communication and public participation in planning are institutionalized. These are developments to be proud of.

Helander and Sundman warned of institutionalized participation, though. They saw it potentially leading to pseudo-participation, which presents the public with virtual options, but no real alternatives that have radically different consequences. True participation necessitates open, versatile and informed public debate. That is the key to better decisions. (Even then, I am afraid, there looms a risk that people prioritize shortsighted individual benefits at the expense of common good.)

Open questions in conservation

Kenen Helsinki posed a question on renovation that still seems to haunt: is light renovation possible? In the 1970, the building regulations did not distinguish between old and new buildings. That is, an old building needed to be modernized thoroughly to meet the standards of new buildings, which makes restoration or extensions expensive. Today, the law distinguishes between new building and renovation, but requires expertise to judge the sufficient standard of upgrade. In practice, it errs on the side of safe standard regulations easily.

The ideology of restoration has changed, too, in 50 years. Vilhelm Helander had a subsequent influence on it through his later work. From the façadism of the mid-20th century that Kenen Helsinki mocks, layers of history and cultural heritage value of buildings, neighbourhoods and landscapes are seen more holistically. Finding a middle ground between of renewal and restoration remains challenging. Helander himself said recently “deconstruction is an honourable death and a better option than spoiling a building” (my translation). I interpret the quote out of the context, since the article is behind a pay wall, but I take it to indicate a dogmatic view on restoration. It echoes UNESCO’s Venice Charter of 1964, article 12 that states “Replacements of missing parts must integrate harmoniously with the whole, but at the same time must be distinguishable from the original so that restoration does not falsify the artistic or historic evidence.”

The Venice charter has become a canon of restoration, never mind that historic buildings have often been through interventions and adaptations. Contemporary idea of conservation is increasingly about sustaining cultural assets than protecting the appearance of monuments (this, too, is a shift to human-centric planning). The Venice Charter dogma leaves out a range of possibilities of reuse. Is it not sometimes more environmentally friendly than deconstruction? Could there be more experimentation in renovation?